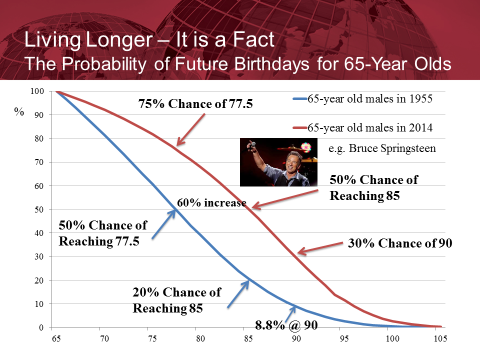

Americans are living longer and retiring earlier. But how, as an individual or as a country, can you finance a 30-year retirement with a 40-year career? Stanford Professor John Shoven recently visited UCSD and presented some interesting policy suggestions.

Probability that a 65-year-old male will live to the age indicated on the horizontal axis as of 1955 (in blue) and 2014 (in red), along with one example of a 65-year-old male in 2014. Source: interesting policy suggestions.

Professor Shoven noted that the current structure of Social Security in some cases amounts to a pure tax on those who work for more than 35 years in order to transfer those funds to individuals who retire early. He suggested that one change we should consider would be to recognize the status of “paid-up workers.” The idea is that if you’ve already put in 40 or more years of paying into Social Security, at that point your personal Social Security bill would be declared to be paid in full, and neither you nor your employer would be asked to make any more Social Security contributions for as long as you continue working. This would create more incentive for older citizens to keep on working and for employers to want to hire them.

I am deeply skeptical of claims that any cut in tax rates could actually produce an increase in tax revenue. But there is at least some offset in this case. If some people work longer than they otherwise would as a result of Shoven’s proposed change, while there would be less Social Security taxes collected from those individuals and their employers, the IRS would collect future income tax from those people that they otherwise would not get. And a number of academic studies (e.g., [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]) have concluded that the decisions of individuals to keep working in their later years can be quite sensitive to their take-home wage, meaning that the income-tax offset could be significant. Moreover, in research with Goda and Slavov Shoven proposed a combination of the “paid-up” exemption along with a number of other changes to benefits and contribution formulas that would be revenue neutral and on net encourage people to use some of the extra years that improving medicine has given us to keep on contributing.