Doug Kass wrote a very interesting piece this week on the bond market:

“As overvalued as I believe the U.S. stock market may be, fixed-income instruments may be even more overvalued.

Yesterday the 10-year note was yielding 2.21% — the lowest yield since last Nov. 11 — and the long bond’s yield is down to 2.88% after weak core consumer price index (CPI) and retail sales were released on Good Friday, when the markets were closed.

This decline in yield and rise in bond prices may be the last opportunity for a generation to sell fixed-income positions. Indeed, bonds may now represent the single most overvalued asset class extant.”

Before I start getting a bunch of “hate mail,” let me state that I greatly respect Doug’s opinion. In this case, however, I simply have a differing view.

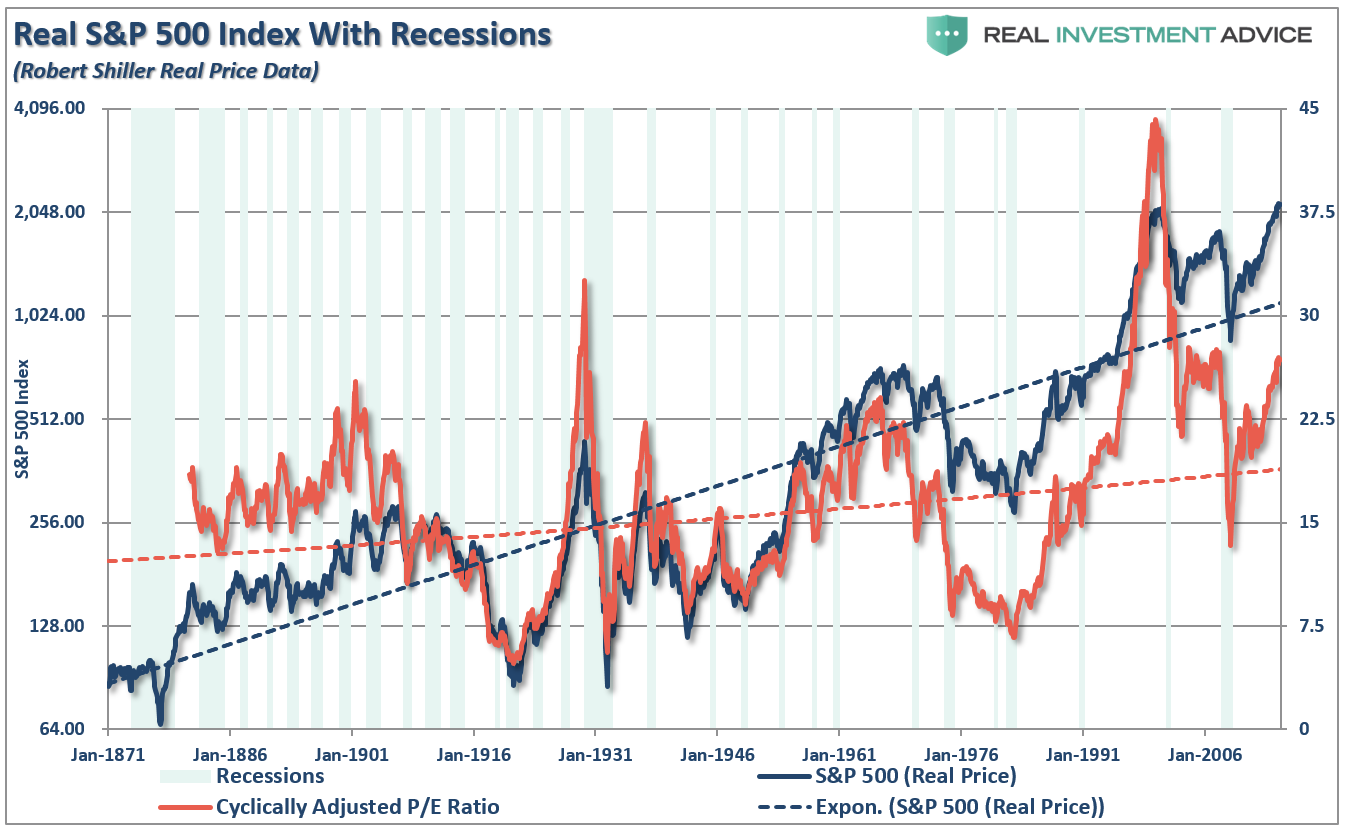

Both Doug and I agree that stocks are indeed overvalued. Since investors pay a price for what they believe will be the future value of cash flows from the company, it is possible that investors can misjudge that value and pay too much. Currently, with valuations trading at the second highest level in history, it is not difficult to imagine that investors have once again overestimated the future earnings and cash flows they might receive from their invested capital.

However, bonds are a different story.

Unlike stocks, bonds have a finite value. At maturity, the principal is returned to the holder along with the final interest payment. Therefore, bond buyers are very coherent of the price they pay today, for the return they will get tomorrow. Since the future return of any bond, on the date of purchase, is calculable to the 1/100th of a cent, a bond buyer is not going to pay a price that yields a negative return in the future. (This is assuming a holding period until maturity. A negative yield might be purchased on a trading basis if benchmark rates are expected to decline further and/or in a deflationary environment.)

Given that bonds are loans to borrowers, the interest rate of a bond, at the time of issuance, is tied to prevailing interest rate environment. In this discussion, we are primarily addressing the 10-year Treasury rate often referred to as the “risk-free” rate.

However, the price of an existing bond, traded on the secondary market, is determined by the difference between the coupon rate and the prevailing interest rate for the type of obligation being considered. The benchmark rate acts as the baseline. Let’s use a very basic example.