The first few days of any calendar month are now flooded with PMI data. Mostly due to Markit’s ongoing and increasing partnerships, we now have access to economic or business sentiment from and for almost anywhere in the world. It isn’t clear, however, if that is a good or useful development.

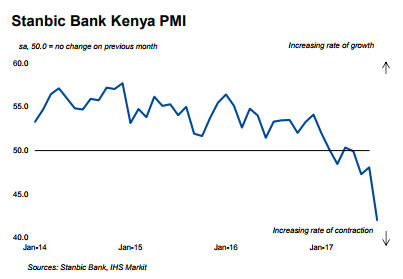

For example, we can see quite plainly that there is a whole bunch of trouble brewing in Kenya. The Stanbic Bank/Markit Kenya PMI fell to a record low 42.0 in August (the index history start only in 2014). Since late last year, sentiment has turned more and more negative mostly on political turmoil. There was first a tense election campaign culminating in a vote last month whose results were then nullified by the country’s Supreme Court.

Whereas that particular PMI might most visibly match the general economic circumstance, the rest of the PMI’s this month for last month have been more mixed – often in the same country (or continent) at the same time.

Before Markit’s big entry into the economic data business, there was the Institute for Supply Management (ISM). Its sentiment survey has a very long track record and is often given serious weight in the most orthodox models (at least it was until 2015 when it started to suggest the “wrong” direction).

The ISM’s Manufacturing Index PMI shot up to 58.8 for August 2017. That was the highest index value since a bunch of 59’s in the summer of 2011 (just before that downturn would form). It was slightly better than the peak in 2014.

Markit’s US Manufacturing PMI, however, is at the other end of the spectrum in August. That particular sentiment index remains near recent lows, more 2016 than what 2017 was thought to be. Unlike the ISM, this version turned lower and quite sharply at the start of this year and has yet to suggest anything more than that.

The two are not going to agree exactly on manufacturing conditions, but in this case they are quite and significantly far apart.