Goldman is out with their weekly piece documenting the conversations they’re supposedly having with clients and this week’s installment is pretty interesting as it touches on a particularly important debate about what the best use of corporate cash is.

As you’re undoubtedly aware, the corporate bid (i.e. buybacks) has been a key pillar underpinning U.S. equity demand over the past several years and more than a few folks have bemoaned the fact that central bank largesse has created an environment that encourages financial engineering. That involves simply leveraging the balance sheet in order to return cash to shareholders and obviously, buying back shares is a “good” (scare quotes are there for a reason) way to inflate the bottom line. When the cost of debt is de minimis and management’s compensation is equity-linked, the stage is set for perverse incentives to take over, and the longer that persists (enabled by central banks), the more out of control it gets.

Before long, you end up in a completely untenable situation where stocks have been levitated by buybacks and credit spreads are completely disconnected from measures of corporate leverage. Alas, such is life in the post-crisis monetary policy regime.

So is that dynamic set to change? Yes and no, according to Goldman. Consider this:

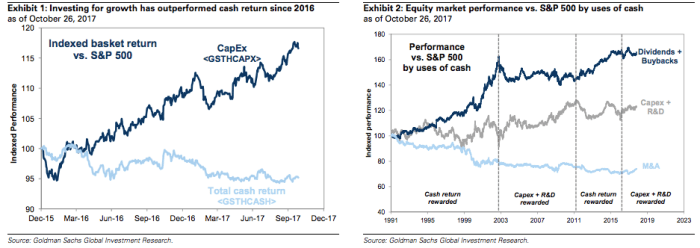

Despite a long track record of investors rewarding companies returning the most cash to shareholders, recently investors have preferred companies investing for growth. Since the start of 2016, our basket of stocks with the highest spending on capex and R&D has outperformed our basket of stocks with the largest buybacks and dividends by 21 pp (+17% vs. -5%). In 2017, the outperformance has totaled 11 pp (+7% vs. -3%).

Such underperformance of cash return strategies is uncommon. Since 1991, our sector-neutral factor of S&P 500 stocks with the highest trailing combined dividend and buyback yields has returned an annualized 15.5% versus 13.8% for the top capex and R&D spenders and 13.0% for S&P 500 (see Exhibits 1 and 2).