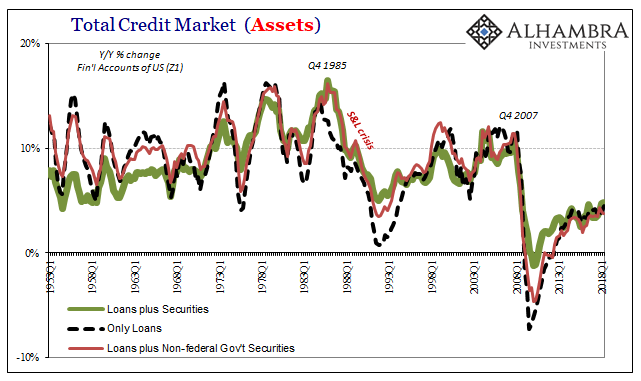

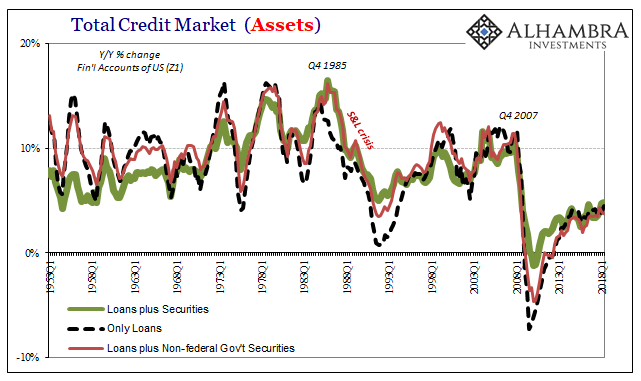

Too much debt. Deleveraging. The debate over the “right” size of the credit market isn’t going to be solved. Like it or not, the US and world economy has been propelled by debt for a century. The domestic credit market’s highest growth rates are found not during the housing bubble of the 2000’s but during and after the Great Inflation of the seventies/eighties.

Misconceptions abound, mostly because Economists have been off studying exclusively mathematics all this time rather than economies and the money makes them go. One of the most striking aspects of this modern system is how the line between money and credit has blurred; a lot of what might be counted strictly as debt is at the same a monetary instrument (collateral in repo, as one example).

The Federal Reserve’s Financial Accounts of the United States (Z1) updated for Q2 2018 show that nothing has changed. Booming economy or not, the credit market still isn’t in it. It continues to grow, as do many important variables, but like a lot of them, it isn’t the same thing as growth.

Believe it or not, the peak rate for credit growth came in Q4 1985 not the top in Q4 2007; though those two particular peaks do share a lot in common. What followed both were banking dislocations that greatly altered the way in which the system would work, or wouldn’t work.

After 1985, the S&L crisis ended up transforming the banking system from depository to wholesale, leaving the commercial bank side of things to push the eurodollar system to its fullest. That meant outside as well as inside the US.

After 2007, everything has just been shut down. Nothing has mattered which might get it restarted again.

Just as the Kansas City Fed noticed in March that housing never recovered from the last bust, the financial system didn’t, either. The two things are very much related, not that any central bankers would identify this latter half of the problem. Even though Z1 is a Federal Reserve series, it isn’t apparent that officials actually use it.