Key Takeaways

- NFTs have become the status symbol of the crypto rich, with sought-after pieces selling for millions of dollars.

- Trading volumes and floor prices for NFTs have soared in recent months.

- Tokenized digital art and fine art share some similarities in the way they are valued.

As NFTs sell for millions of dollars, many onlookers are wondering why. How can tokenized JPEGs of rocks have any value? The reason, it turns out, may not be all that controversial.

NFTs Go Mainstream

On Mar. 11, 2021, one of the world’s premier fine art auction houses, Christie’s, sold its first purely digital NFT artwork. The item in question, Beeple’s “Everydays: The First 5,000 Days,” sold for a record-breaking price of $69.34 million. It was paid for in Ethereum. The buyer was Vignesh Sundaresan, also known as MetaKovan, a Singapore-based crypto investor and founder of the largest NFT fund, Metapurse.

That changed with the recent introduction of non-fungible tokens or NFTs, a new type of cryptocurrency that first appeared on the Ethereum blockchain. NFTs are unique units of digital data that get stored on a blockchain like Ethereum, and they can be used to tokenize digital art, music, or any other type of asset. Unlike assets like BTC or SOL, each asset is unique, which means they are not interchangeable. NFTs are useful because they offer a way to verify the ownership, authenticity, and scarcity of an asset.

Beeple’s landmark Christie’s debut brought unprecedented attention to NFTs and acted as a catalyst that propelled the technology into the mainstream. Renowned tech investors and entrepreneurs (Mark Cuban, Gary Vaynerchuk), celebrities (Lindsay Lohan, Logan Paul), musicians (Aphex Twin, Grimes), sports players (Steph Curry, Tom Brady), and even major corporations (Visa, Coca-Cola) are all either buying into or experimenting with NFTs in one way or another.

Though the NFT market suffered a crash along with the rest of the crypto space in May, momentum soon returned for what many crypto followers dubbed “NFT summer.” In August alone, the largest NFT marketplace OpenSea registered more than $3 billion in trading volume. CryptoPunks, arguably the most iconic NFT collection on Ethereum, also surpassed $1 billion in lifetime transaction volume. And digital rocks from EtherRocks, one of Ethereum’s earliest NFT collections, hit a floor price of over $2 million. Such staggering numbers raise several questions about the value of NFTs. Why are NFTs valuable? Who is spending fortunes on penguins, rocks, and pixelated Punk avatars? And more importantly, why?

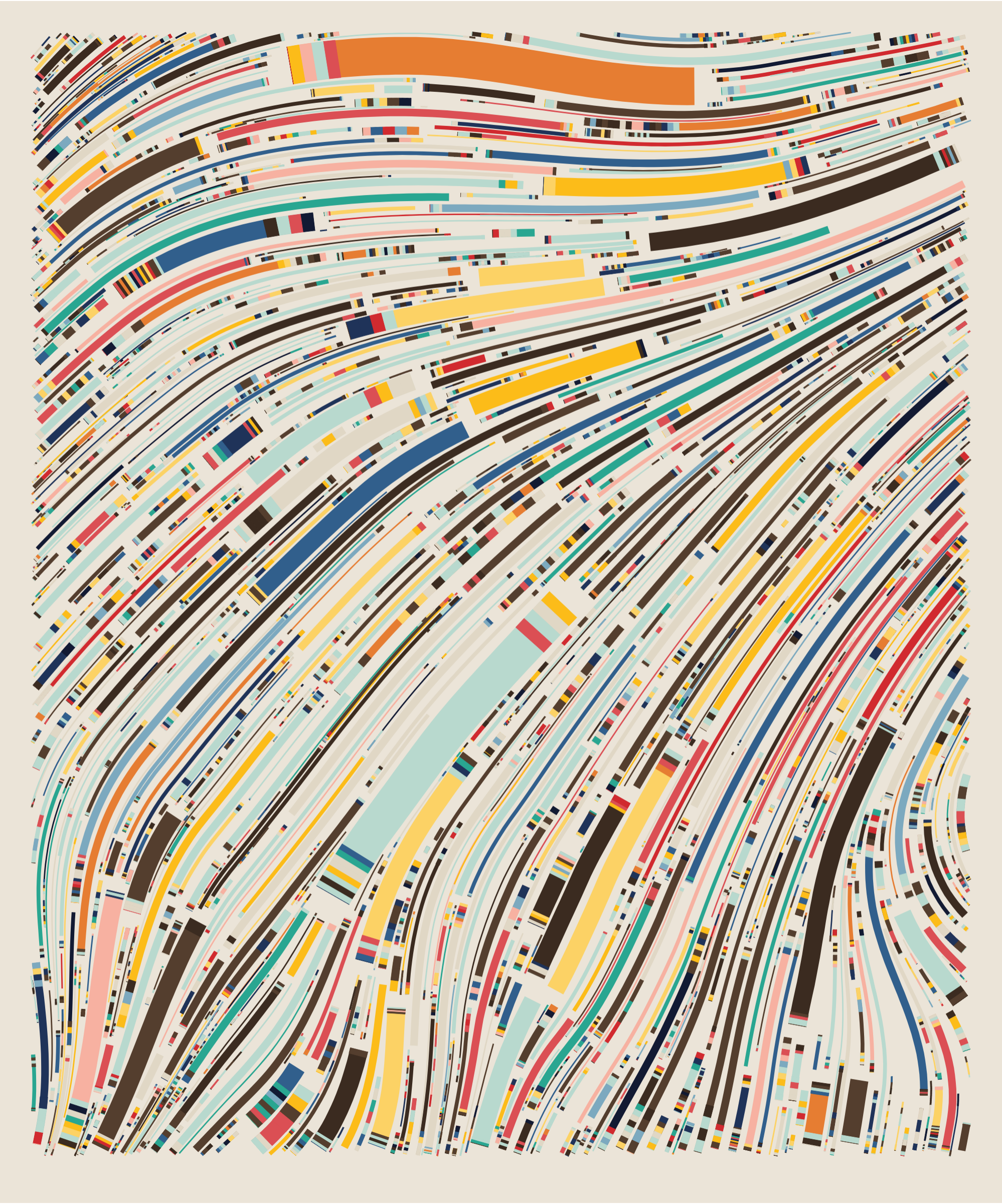

While NFTs can encompass anything from in-game items to music, metaverse merchandise, lists of words, and other kinds of digital collectibles, digital art is the niche that’s seen the biggest growth this year. Avatar projects like Bored Ape Yacht Club have exploded in popularity, while the generative art platform Art Blocks has shone the light on a new form of creativity within the art world.

Fine art is traditionally defined as art created solely for aesthetics and is distinguished from decorative or applied art, such as metalwork or pottery, which also has to be functional. Beeple, FEWOCiOUS, CryptoPunks, Pudgy Penguins, Bored Ape Yacht Club, and Art Blocks NFTs fall within this category as they’re creative works that are primarily used for aesthetics.

While anyone can enjoy an artwork displayed on OpenSea or download the JPEG, not everyone can own the original NFT. Tokenizing an asset on a public blockchain creates a way for anyone with an Internet connection to verify its authenticity and ownership. In some senses, owning an NFT of an artwork versus owning a JPEG of the same artwork can be compared to owning an original Andy Warhol versus owning a poster of the piece.

While the artwork itself may serve no purpose other than aesthetics, the act of purchasing it does. Economic literature distinguishes between two types of consumption values: hedonic and functional. Hedonic products are consumed mostly for affective or sensory fulfillment, while functional products are for utilitarian goals. Given that anyone can “consume” NFT artworks for hedonic or sensory fulfillment purposes without purchasing them, collectors may be more motivated to purchase them for utilitarian purposes.

But what is the utility? Is there a logical reason for someone to spend seven figures on an animal avatar or digital rock? Costly signaling theory would suggest the reason is to flex. Almost all animals benefit from altering the perceptions, behavior, and psychology of others in their environment in ways that benefit themselves. This is particularly true for social animals like humans, who regularly employ different tactics like investing in costly signals to enhance their perceived attractiveness, formidability, or status.

As humans are capable of higher-order thinking, as targets or receivers of these signals, they often verify their validity before accepting them at face value. This is why flexing must be costly in order to work. Individuals who possess certain socially desired qualities will invest more in signals than those who lack them, thereby producing signals that are difficult or unreasonably costly to fake.

Purchasing NFTs of pixelated punks for hundreds of thousands of dollars a go is an example of costly signaling. Ownership or provenance cannot be faked, the costs are easily auditable, and the pieces offer little utility other than flexing. This explains why NFTs have quickly risen to become the luxury status symbol of choice for crypto’s nouveau riche. After all, nothing says “I’ve made it” like splurging north of a million dollars on a digital picture of a rock.

Opulence, Envy, and Crypto’s Nouveau Riche

Just as old money homes are filled with expensive artworks, collectibles, and golden toilets, crypto’s nouveau riche like to fill their digital wallets with NFT artwork. Pointillism has become pixelism.

Powerful people have used opulence to symbolize their status since the dawn of civilization. In more modern times, opulence also represents success. Put differently, as the popular YouTuber ContraPoints pointed out, “opulence is the aesthetic display of success”—a costly signal designed to provoke feelings of awe and envy within one’s group of peers.

Envy, when stripped of its inherently negative colloquial connotation, is directly tied with the human universal of concern for relative status. Eric Falkenstein, economics Ph.D. and a renowned macro investor, hypothesized that humans are more concerned about relative wealth than absolute wealth, and that envy is a “more evolutionarily plausible self-interest mechanism than greed because it is more robust.” Presenting the notion of self-interest as a status symbol, he added:

“Economists generally think of self-interest as maximizing the present value of one’s consumption, or wealth, independent of others… But what if economists have it all wrong, that self-interest is primarily about status, and only incidentally correlated with wealth? A lot, it turns out.”

According to him, status signaling is about putting oneself in a rank. “Envy is simply another way to approach the status game, noting the focus on those above,” he argued. Sharing Falkenstein’s view, English art critic brushed on the subject of flexing in his book Ways of Seeing. He wrote:

“Being envied is a solitary form of reassurance. It depends precisely upon not sharing your experiences with those who envy you.”

The pleasure of purchasing luxury goods such as fine art NFTs may not be a means to an end but an end in itself—the feeling of having a superior status, at least for a moment.

NFTs as Satire

One question that naturally follows from this topic is why crypto’s new money are choosing NFTs of pixelated punks, poorly drawn rocks, and cartoon depictions of apes over, say, classical artworks, gothic mansions, or golden faucets. It’s because the status-seeking game is played within a group of peers, and crypto’s nouveau riche do not align themselves with the established fiat aristocracy.

The crypto industry was built as an act of rebellion against the fiat system’s injustices and inefficiencies. It is, in essence, an economic experiment with inherent political and ideological foundations.

In an interview with the BBC, former Christie’s auctioneer Charles Allsopp said that buying NFTs “makes no sense” because “the idea of buying something which isn’t there is just strange.”

Beyond a mere flex, the act of spending millions of dollars on a JPEG of a rock is, in principle, satirical—an act of both mockery and rebellion. It’s rebellion against the superfluous wealth inequality this JPEG-flipping generation believes it has nothing to do with, and mockery of its wealthy, gatekeeping elites.

From a cultural point of view, the NFT world is an inverse of the traditional art world. At its worst, the traditional art world is exclusionary, pompous, and self-righteous. NFTs, meanwhile, can be tacky, gaudy, and garish—the equivalent of Mona Lisa in a leopard skin dress. In Fierce: The History of Leopard Print, author Jo Weldon described tacky as a concept that refers to “the lack of cultivation or the resistance to taste” that often refers to “tastes that are not suitably conservative.”

That’s what EtherRocks are—a stubborn resistance to taste. Unlike much of the traditional art world, the NFT world embraces its absurdity. Nobody in crypto would talk about an EtherRock the same way Arne Glimcher, one of the world’s leading art dealers, describes Mark Rothko’s “White Center (Yellow, Pink and Lavender on Rose)”. “It is a wonderful painting. What Rothko was really interested in is the idea of an almost formlessness use of color to transmit pure emotion,” he told Alastair Sooke in the BBC documentary “The World’s Most Expensive Paintings.”

NFTs, then, may not be all that different from traditional art after all. Whether it’s tokenized digital art or a physical painting from a world-renowned artist, in the end, the value is determined by what someone is willing to pay for the piece and its associated flexing rights. A crucial difference with NFTs, of course, is the transaction for the sale will always be there on the blockchain for everyone to see.

Disclosure: At the time of writing, the author of this feature owned ETH.